In a previous post, I tried to create a “Call to Arms” for Scrum Coaches and Trainers to do much more than simple, team-based training. While that seems to be a great deal of our focus, I don’t think it’s creating the environment and landscape for agile methods and Scrum in particular to “Transform the world of work”.

In early May 2014, I was at the Scrum Gathering in New Orleans and hanging out with a significant part of the CST and CSC community. A great deal of the discussion on how to “Transform the world of work” is focused on training and certifications. To be honest, I’m quite disappointed on the lip service that is largely given to the world of agile coaching. And coaching “downward”, toward the team, is most of that coaching focus.

If you don’t know, I’ve got some opinions about Scrum, the Product Owner role, Backlogs, and User Stories. I’ve written a book about Product Ownership and I spend a great deal of my time up to my eyeballs in stories and backlogs at various clients.

One of the things that frustrates those clients is that there are very few “prescriptive rules or firm guidance” when it comes writing stories and crafting Product Backlogs; in many ways, it’s more art than science. It’s also a practiced skill that gets better the more you actually do it—of course as a team, which is also true of agile estimation.

No is a very tricky word. I often talk about agile teams needing to “just say No” to various things. For example:

- If their Product Owner expects them to deliver more than their capacity

- If their Boss asked them to deliver faster and it would violate their Definition of Done agreements

- If a Team Member continues to “go it alone” and refuses to collaborate as a team

Then I’m looking for the team to say No. Whenever I bring this up in classes or presentations, I always get pushback. Always. Usually its not based on the situation, but to the word. It seems No is a word that nobody likes using in the workplace.

There’s a wonderful video by Henrik Kniberg where he explores the role of the Scrum Product Owner. In it he makes the point that the most important word that a Product Owner can use is No. That it’s incredibly easy to say – Yes to every request. To pretend that things are always feasible or easy. But that No is important. No implies that trade-off decisions need to be made on the part of the customer or the organizations leadership. That the word leads to thinking, discussion, and decision-making.

It’s sort of a chicken and egg problem in many agile teams—that is the notion of trust.

- Do you give the team your trust as an organization? Or do they have to earn it over time?

- And if they make a mistake or miss a commitment, do they immediately lose your trust? And then have to start earning it again?

- And is trust reciprocal, i.e., does the organization need to gain the trust of the team? And if so, how does that work?

I want to explore trust in this article. I’ve done it before, but an interview by Jeff Nielsen inspired me to revisit it.

I’ve just returned from my first trip to China. I attended the TiD 2014 Conference, which was a consolidation of 3 specific conferences:

- AgileChina

- ChinaTest

- SPIChina

It’s the first year for the conference’s to be united in this way. For example, this was the first year for AgileChina, but the third or fourth year for ChinaTest.

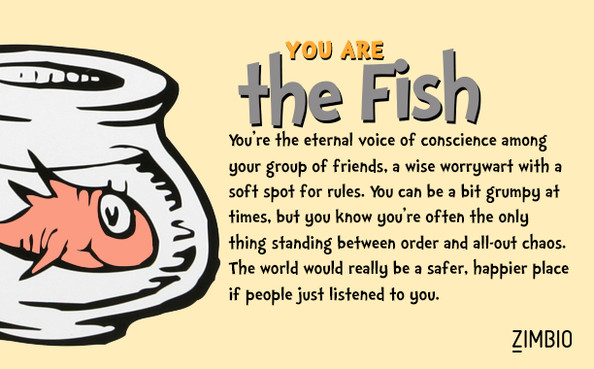

There's an interesting website called Zimbio that runs a variety of fun surveys. I just filled in a Dr. Seuss character survey to see which character I most resemble. The returns are in and...tada...I am closest to:

the Fish

You're the eternal voice of conscience among your group of friends, a wise worrywart with a soft spot for rules. You can be a bit grumpy at times, but you know you're often the only thing standing between order and all-out chaos. The world would really be a safer, happier place if people just listened to you.

Now if only I knew the Fish well enough to resemble that remark :-)

Stay agile my friends,

Bob.

I presented at a local professional group the other evening. I was discussing Acceptance Test-Driven Development (ATDD), but started the session with an overview of User Stories. From my perspective, the notion of User Stories was introduced with Extreme Programming as early as 2001. So they’ve been in use for 10+ years. Mike Cohn wrote his wonderful book, User Stories Applied in 2004. So again, we’re approaching 10 years of solid information on the User Story as an agile requirement artifact.

My assumption is that most folks nowadays understand User Stories, particularly in agile contexts. But what I found in my meeting is that folks are still struggling with the essence of a User Story. In fact, some of the questions and level of understandings shocked me. But then when I thought about it, most if not all of the misunderstanding surrounds using user stories, but treating them like traditional requirements. So that experienced inspired me to write this article.

I’m wondering if you think this post will be about the Scaled Agile Framework or SAFe? Well, it’s not. Before there was SAFe, there was good old-fashioned “safety” from an agile team perspective. And that’s where I want to go in this piece. So just a warning that no scaling will be discussed :-)

Within Retrospectives

I often advise teams and organizations that are contemplating “going Agile” to consider safety as a factor when running their retrospectives. I share the “Galen-rule” around not inviting or having “managers” in the teams’ retrospective.

I was once working with a peer agile coach and we were discussing the role of the coach within agile teams. His view was that it was as a “soft, encouraging, influencing” role. That at its core agility is about the team. And the team in this sense is…self-directed.

He also emphasized that taking a more direct or prescriptive approach in our coaching would be anathema to good agile practices. That it was draconian and dogmatic.

He was actually a leader of this firms coaching team, so he had tremendous influence over a team of ten or so agile coaches. I was one of them and I sometimes struggled with his view and approach.

I came across a wonderful post about changing the daily stand-up meeting. It aligned incredibly well with how my own thinking has evolved of late. It’s by Cheryl Hammond from Northwest cadence. She makes some points around reframing the questions and/or focus of the daily standup meeting.

While I don’t agree with the entire premise of her recommendation, she did make me think some more about it and most of what she said aligned with my own evolving position.